About five hours from where I currently live is an old fort. Its ruins, to be precise. Hidden in the backyard of a small fishing village, it is well-kept but empty, with a noticeable lack of the swarms of tourists and pre-wedding setups that such places are wont to have nowadays.

I have always been fond of ruins. Perhaps it is the result of watching too much Indiana Jones, but there is something about these old places, they are exciting yet morose— with a certain melancholy that hides stories from before.

I would love to go on adventures through the ruins of an old castle like ol’ Indi, but I like simply walking through them as well. I love looking for traces of life in the bones left behind: groves that once held door frames, lacerations in the walls that were once filled with inlaid stones, overgrown weeds covering places where the laughter of children rang out. I love Sherlock-Holmes-ing my way back into their lives: imagining the effect of the flickering lights that lit up corridors back before gas lamps were a thing; noticing how stones were used— stronger ones for foundations and permanence, softer ones to carve and decorate; reverse-engineering the lay of the site— how many sitting rooms did they have, where was the kitchen, who had permission to enter?

I call these places ‘ruins’, but I don’t quite think they are ‘ruined’ in the way one might be led to believe. I mean, yes, these ruins aren’t exactly palaces today, but… that does not mean they aren’t something.

There are so many ‘ruined’ places that function differently than what they were planned for. And also several ruined places that continue to function despite the age and disrepair.

Vic Market in Melbourne is probably among my recent favourites. It came up in the late 1800s, and has stayed put since then. And it has evolved with the times. Its old walls are intact, rows of running red bricks hold up cornices that are more than a century old, while the shops below belong to today: awash with LED lighting and offering menus on QR codes.

This is admirable, but not unique. Closer to (my current) home, the Khanderao Market in Baroda is the same, a relic of the past that continues to exist (and exist well) in the present. It is a megalith, inaugurated in 1935, and built to last. It is shaded and bustling, with traders of food and spices sitting cross-legged, ready to haggle and barter their wares. Bulbs have replaced candlelight now, but the work that happens is the same. Life is rarely different about the essentials.

And of course, we have numerous examples of heritage hotels— palaces and family homes spruced up and leased out to hospitality chains, or offered as residencies for artists, away from the city.

What I mean to say is, things need not exist in the state they were in for them to be useful. Or even to be in the state they were designed for. The old ruins near my home might not be a famous port anymore, but they’re home for so many plants and animals. They are a getaway for people aching for some quiet. They’re also a hangout for college kids, a ‘third place’ in a world which is slowly losing them. It is not what the builders planned the fort to be, but… it is what it is.

Louis Kahn, the famed American architect (designer of the Salk Institute, the IIM-A campus, and the Bangladeshi Parliament building, among others) was well known for his work with bricks, specifically, the use of the arch.

Kahn has a wonderful quote attributed to him:

‘You say to a brick, “What do you want, brick?” And brick says to you, “I like an arch.” And you say to brick, “Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.” And then you say: 'What do you think of that, brick?' Brick says: “I like an arch.”’

[Photo by Cemal Emden, sourced from here.]

It’s a wonderful quote, and captures so very well the sanctity with which he approached his work. Kahn was phenomenal, and his works are as grand and monumental as the legacy he left behind.

But you know what I say? That same brick told my old uncle that it wanted to be a doorstopper. And guess what? That brick works just as well doing that. Best doorstopper you’ll ever see.

Its brickness remains, whether arch or weight.

What I am saying is, I think, that what is ruined is not always lost. It may not be its old self, or function as it was meant to function, but it still is. And it can be restored, or refurbished, or reused, as long as it has good bones.

I think this hits a bit close home because right now, I am staring at the ruined castle of my own life, inlaid stones gone, plaster peeling, solid walls crumbling.

But the foundation is in place, it has good bones— something will come of it yet.

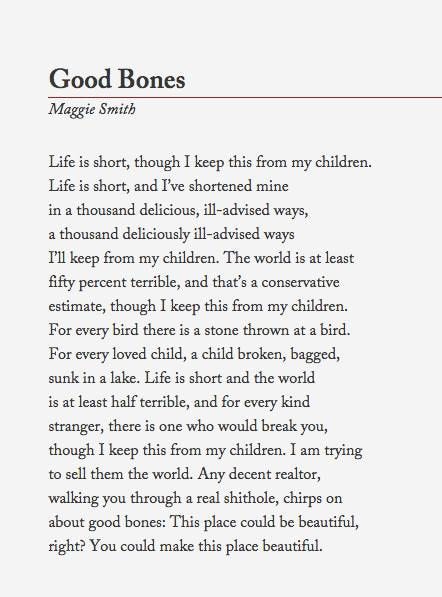

[good bones, maggie smith].